HARI SREENIVASAN: This week, we’ve brought you three reports from inside South Sudan, a nation ravaged by war, famine, and a place where rape is used as a weapon. Tonight, we turn our focus to neighboring Uganda, which has an open door to refugees. But with hundreds, sometimes thousands each day pouring across the border, Uganda’s openness is being put to a test.

Special correspondent Fred De Sam Lazaro reports.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: On a recent afternoon, refugees from South Sudan sang songs of praise and thanks. These are the newest arrivals from the brutal civil war in their young country.

The South Sudan border is just about a mile down this road here. Some 500 people walk in each day into Uganda. There’s no sign indicating they’ve arrived. The first evidence they’ll have a safe night to sleep are these white tents here put up by the United Nations.

Water is provided but no food. That will have to wait for at least another day when they reach settlement centers to be registered. Some people told us they hadn’t eaten for days. These women arrived after a five day walk through the bush, found an open spot on the floor and quickly collapsed in complete exhaustion.

Some refugees tell harrowing stories about the violence they’ve seen, much of it ethnically based.

EMMANUEL KENYI, Refugee: The Dinkas is killing us. They are killing the civilians.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: They are killing you just because you are not a Dinka?

EMMANUEL KENYI: Yes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Nearly 600,000 refugees have entered Uganda since July when new fighting from the civil war erupted, and the flow continues unabated. Bidi Bidi, the world’s largest refugee settlement with 300,000 residents, about the size of Pittsburgh, was closed to new arrivals in December to prevent overcrowding.

Invepi, about 30 miles from the border, was opened two months ago. Already 62,000 people have moved in, a number expected to reach the 110,000 capacity by late May or June.

The overwhelming numbers are straining relief efforts. People wait in line for hours, occasionally days on end just to get registered. And tensions are rising between the newcomers and Ugandans from nearby communities.

We arrived at Invepi shortly after a skirmish broke out between refugees and locals. This young refugee was bloodied and eventually taken away by ambulance.

U AYE MAUNG, Field Director, U.N. High Commission for Refugees: We’ll take good care of him.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: U Aye Maung is field director the U.N. High Commission for Refugees at Invepi.

Is that a concern for you, the tensions between the local communities and the refugees?

U AYE MAUNG: Yes, we have seen some tensions arise between people. The concerns are valid. There are protection issues. We have a large number of children, women and single boys, young girls. They need protection. They need space, safe space so they can be able to go to school, they can able to do their basic rights in the settlement area.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Such hostility is relatively new in a country whose official policy has been to integrate refugees.

It looks like any other African village rather than a refugee camp, and that’s the point. Uganda’s open door policy insists that refugees be placed in settlements, and not camps, acknowledging that most families will stay for some time, and given a small plot of land that they can start to cultivate, build a small dwelling on it, and they’re free to seek opportunities anywhere else in the country.

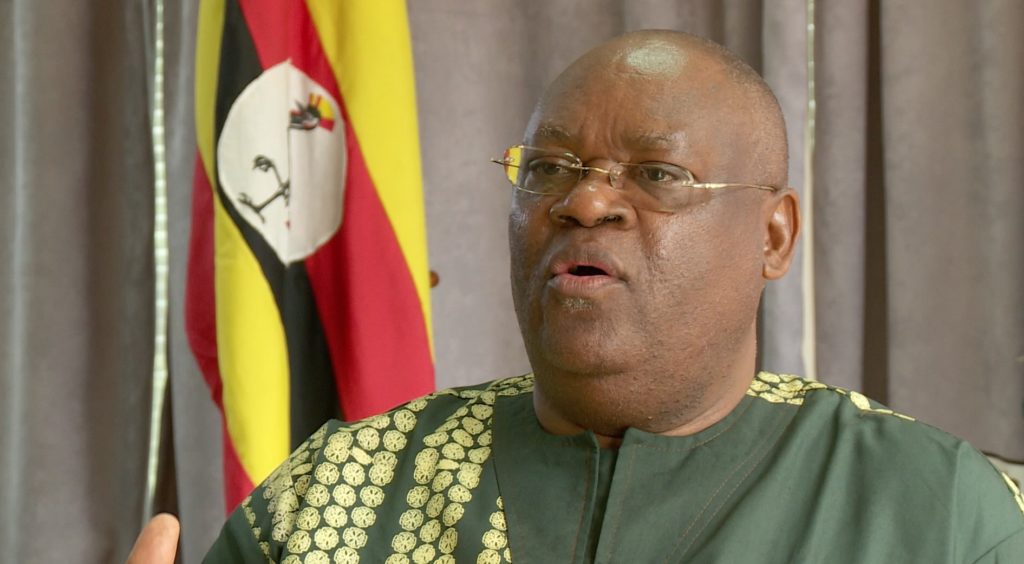

SHABAN BANTARIZA, Uganda Government Spokesman: As a people who have suffered before, we do not think that we should shut out anybody who is running away for security.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Shaban Bantariza is a spokesman for the Ugandan government. He says his country was itself once an exporter of refugees when it was wracked for years by war. Uganda will continue to provide what it can, he says, but the anger expressed by some of Ugandans is understandable.

SHABAN BANTARIZA: They feel disadvantaged and they have expressed that. They feel that their inability to get sufficient drugs, their inability to have enough food is because of the influx of refugees. So, naturally, they feel agitated. But we are trying to work on that.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: At the settlements, food is still available to the newest arrivals. But rations have been cut in half for people who have been here for several weeks.

Water must be trucked in at huge expense. The onslaught has been so abrupt, there hasn’t been time to survey land and drill wells for clean water.

The rationing of food was apparent when we talked with James Ken. He and his family of seven walked for three weeks to reach the safety of Uganda. They now live in this tent constructed of tarps.

He’s grateful for the welcome he’s received but says there isn’t enough food to go around.

You run out sometimes?

JAMES KEN, Refugee: I run out completely. Even now, as you have seen, there’s nothing on the fire.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: There’s nothing cooking today?

JAMES KEN: Yes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So what will the children eat today?

JAMES KEN: Then I have to run and I see other solution where I can borrow from the neighbors.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Apparently, the neighbors did help, with this maize flour for the next family meal.

The U.N. estimates it will cost $840 million to deal with the refugee crisis in Uganda this year. But El Khidir Daloum of the U.N.’s World Food Program says agencies like his are facing a severe shortfall.

EL KHIDIR DALOUM, World Food Program: We are only 40 percent of what we need. We appreciate all the support we have received from or donors so far. But we appeal to all the donors that they need to increase their pledges to us and to other actors, so that we address especially the life-saving needs for the refugees in the settlements.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The government and U.N. officials say things are approaching a breaking point.

SHABAN BANTARIZA: The strain is definite, no doubt about that. And that’s why we try to engage everybody, in and out of Uganda, the international community. Refugees cannot be the responsibility for Uganda alone.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: It’s a global responsibility.

SHABAN BANTARIZA: It’s a global responsibility.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Ultimately, of course, the Ugandan government and the refugees say the solution is for conditions to stabilize in South Sudan so the refugees can return. That’s certainly the hope of James Ken.

So, you could live here for a long time?

JAMES KEN: Forever. Unless we go back to South Sudan, when peace comes back.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Do you think peace will come back to South Sudan?

JAMES KEN: Well, we don’t know.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: What he does know is a strong sense of deja vu. The 32-year old Ken actually came to Uganda as a child, fleeing earlier strife. He returned to South Sudan 12 years ago when peace arrived, only to flee again just weeks ago. Now, he fears it could take a generation in his family and thousands of others to make the trek back.

For the PBS NewsHour, I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro at the Invepi refugee settlement in northern Uganda.

HARI SREENIVASAN: Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Undertold Stories Project at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

And you can watch all of our stories from inside South Sudan on our website at pbs.org/newshour.

Testing a Warm Welcome

fleeing violence and war in neighboring South Sudan, and the flow continues unabated. The overwhelming numbers of people fleeing violence are straining relief efforts and inciting tensions between newcomers and Ugandans from nearby communities. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports.

Some 500 people walk into Uganda everyday

Water is provided at the border but no food. That will have to wait for at least another day when they reach settlement centers to be registered.

Shaban Bantariza

“As a people who have suffered before, we do not think that we should shut out anybody who is running away for security. … They feel disadvantaged and they have expressed that. They feel that their inability to get sufficient drugs, their inability to have enough food is because of the influx of refugees. So, naturally, they feel agitated. But we are trying to work on that.”

James Ken

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: You run out sometimes?

JAMES KEN: I run out completely. Even now, as you have seen, there’s nothing on the fire.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: There’s nothing cooking today?

JAMES KEN: Yes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So what will the children eat today?

JAMES KEN: Then I have to run and I see other solution where I can borrow from the neighbors.