Geoff Bennett:

To many of his supporters, Leonard Peltier was a political prisoner unjustly punished for his activism with the American Indian movement. To his critics, he is a remorseless killer of two FBI agents 50 years ago, a charge he denies.

In the final minutes of his presidency, Joe Biden commuted Peltier’s sentence, restricting him to home confinement.

Our Fred de Sam Lazaro recently visited Peltier on the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation in North Dakota.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Can you see that screen, or is it too small?

Leonard Peltier, Indigenous Rights Activist:

No, it’s too small.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

His sight is impaired, among several health problems, time in prison compounding the toll of time itself.

Leonard Peltier:

Play welcome home, Uncle Leonard.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

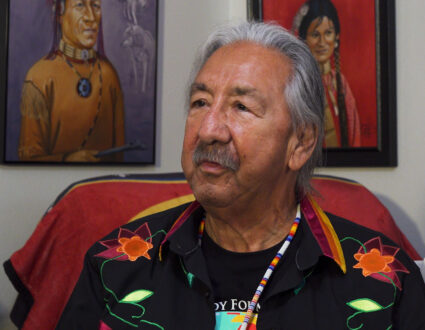

Time has brought helpful technology and, at his home today, Leonard Peltier is surrounded by memories and art, much of it his own work.

Leonard Peltier:

That’s the drawing over right here.

I have always wanted to be an artist. And then I painted murals and stuff before I went to prison. And when I got there, I probably painted two, three, four hours a day. And this guy was a modern-day medicine man.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

That sustained him through the decades in federal prisons, he says, as did moral support of fans and celebrities worldwide.

Leonard Peltier:

This was given to me.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

One prized possession, this sculpture of an ancient indigenous warrior sent to him by then-Bolivian President…

Leonard Peltier:

Evo Morales, the first full-blooded Indian president in this continent. I’m very proud of it.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

This home was bought for him by his supporters, a modest two-bedroom rambler, but after a life in poverty or prison, it’s an unimaginable luxury.

Leonard Peltier:

When I walked into the door, and I said, this is my home, this is what you guys bought me, they said, yes, we — you sacrificed for us. This is yours.

Nick Tilsen, Founder and CEO, NDN Collective: I just want to acknowledge the generation before us. Think about everything that Leonard, AIM, the American Indian Movement, did, his own freedom.

And we’re going to keep calling for Leonard’s freedom.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Nick Tilsen, who heads the indigenous advocacy group NDN collective, helped lead the most recent campaign to bring Peltier home, literally, including a rousing welcome earlier this year.

Nick Tilsen:

They didn’t wait for things to be perfect. They didn’t wait for a strategic plan. When they seen the injustice, they did something about it. And so, for me, one of the big things that’s being a big inspiration from him.

Leonard Peltier:

We were called every goddamn name you could be called, so the public that hate us. No, we weren’t those people.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

At 81, Leonard Peltier is as angry as ever, unapologetic for a lifelong effort to draw attention to the litany of indigenous grievances.

Leonard Peltier:

All we were trying to do was save a race of people from being terminated. They enslaved us, killed us, massacred us, raped our children, enslaved our children.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Leonard Peltier says he felt his first call to activism as a young teen here on Turtle Mountain Reservation in North Dakota, a small, isolated Chippewa community that Congress was considering terminating in the 1950s.

Termination was part of a larger policy of assimilating indigenous people, and it would have ended all federal support for the community here. Turtle Mountain was eventually spared termination, but the young Peltier did feel the sting of assimilation policies, placed when he was 9 in an Indian boarding school.

The children were forcibly removed from their families with the goal of erasing their native language and culture. Many schools were rife with abuse.

Leonard Peltier:

All of our hair was cut off, and they would start indoctrinating us into the white culture and education, whatever you want to call it. And when we continued to be rebellious about it, we would get the hell beat out of us.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Federal policies also relocated millions of Native Americans to urban centers and confiscated vast swathes of mineral-rich lands beyond those ceded in treaties, the legacy, impoverished reservations and an indifferent Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs, which Peltier says, colluded with local tribal governments.

Leonard Peltier:

Land and cattle, they were selling out. We knew that. Almost every tribal government was corrupt back in them days. That’s why we went after them.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

“We” is the American Indian Movement, or AIM, armed self-described warriors who challenged the status quo.

Like the Black Panthers and civil rights and anti-war campaigners of the time, they drew scrutiny from the FBI, particularly on and near the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. In June 1975, two FBI agents and one movement activist were killed in an encounter near an AIM campsite.

Peltier was one of three AIM members charged in the agents’ killing. He fled to Canada, while the other two were tried and acquitted after arguing that they acted in self-defense.

Nick Estes, Professor of American Indian Studies, University of Minnesota: Had he been tried alongside his co-defendants, he probably — we wouldn’t be having this conversation.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Nick Estes, professor of American Indian studies at the University of Minnesota, says, by the time Peltier was extradited back to the U.S., prosecutors changed their strategy and the trial venue.

Estes is one of many academic and legal scholars who’ve questioned its fairness.

Nick Estes:

He just happened to be an American Indian man on the reservation that day in possession of a gun, because they could not actually prove that he was the shooter.

Michael Clark, President, Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI: He’s been unrepentant. He’s been remorseless.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Well, he says that he did not kill these agents, so that would explain his lack of repentance, I suspect.

Michael Clark:

Well, the evidence, the courts, the appellate courts all say differently.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Michael Clark heads an association of former FBI agents. The agency has long vigorously opposed any clemency, insisting justice was served in Peltier’s case.

Michael Clark:

He had 12 separate opportunities for appeals, all of which were denied. You just can’t change the facts of this heinous crime.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Why haven’t they sustained an appeal?

Nick Estes:

The overwhelming influence of the FBI. I mean, it’s easy to just keep saying this. The way that the FBI has intervened not only in his parole hearings, but in these appeals cases, who wants to be the judge that lets off an alleged cop killer?

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

An allegation Peltier insists was false brought by a legal system that has long mistreated indigenous people and one reason he says he’s spurned any plea deal that might have lessened his sentence.

Leonard Peltier:

I’m a sundancer. I took that oath. As a sundancer, I would die for the people if I had to, but I was not going to turn against my people. So I stayed defiant all the 49 years-plus in prison.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

And you say even today.

Leonard Peltier:

Even today. You hear me now. I’m not — I ain’t changed.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Neither have the dire conditions in most indigenous communities and the campaigns for the return of lands for treaty rights.

Nick Tilsen:

We will continue to rise up no matter what basis our people.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Peltier will be there mostly in spirit, not in person, thanks to frail health and restrictions on his travel.

Leonard Peltier:

I can’t go to Grand Forks for medical treatment without a pass or anything over 100 miles. I can only stay so many days. I can’t have a whole bunch of people here visiting me at one time.

I still haven’t seen some of my family.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

And is that your little sister, Betty?

Leonard Peltier:

My little sister Betty, yes.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Aside from reuniting with family members, this twice-married father of seven hopes upcoming treatment will improve his vision so he can resume painting.

Leonard Peltier:

This is going to be my studio.

Fred de Sam Lazaro:

Less certain is his second hope for a full pardon.

For the “PBS News Hour,” I’m Fred de Sam Lazaro on the Turtle Mountain Chippewa Reservation.

49 Years Later

To his supporters, he’s an Indigenous rights activist and political prisoner unfairly targeted by the U.S. government for his involvement with the American Indian Movement. To his critics, most from the FBI, he’s an unrepentant killer of two agents in 1975, a charge he denies. Now, at 81, and after 49 years in prison, Peltier lives under home confinement on North Dakota’s Turtle Mountain Reservation. We visited him there for a rare, candid conversation about his past, his anger, his art, and the cause that still drives him.