Jennifer Ho: the way that we accumulate wealth in America is largely through our homes.

Kirsten Delegard: Once you start looking at racial disparities, housing takes center stage. A lot of these other disparities that people have been talking about for years in terms of education, health, wealth are all rooted in what your access to housing is.

Solveig Rennan: Welcome to Under-Told: Verbatim. I’m Solveig Rennan for the Under-Told Stories Project. We record hours of interviews in our work reporting for the PBS NewsHour, but only a fraction of the conversation makes it onto the broadcast. This podcast series allows us to delve more deeply into the full story, so you can hear changemakers around the world – in their own words.

Fred de Sam Lazaro: Well, you guys have been on quite a journey. What does it feel like right now?

Tim Luckett: Feels great to finally become homeowners.

Melva Luckett: Yeah, that’s a blessing.

Solveig Rennan: Buying a home is a rite of passage, a life-changing step… but in the Twin Cities especially, this crucial key to accumulating and passing down wealth is much harder to come by if you are Black.

Tim Luckett: We were just a little bit nervous that, you know, we wouldn’t close. But just by the grace of God, we end up closing and everything worked out for us

Solveig Rennan: Tim and Melva Luckett are a young African American couple who recently became Minneapolis homeowners. Just 25 percent of Black residents of Minneapolis and St. Paul own their homes. That’s far below the national average, especially considering the Twin Cities are widely regarded as one of the country’s most affordable metros. As far as white residents here, though, 75 percent are homeowners.In the summer of 2021, the Lucketts sat on their new front porch with their daughter, Melani

Tim Luckett: Living and renting your whole life, like why wouldn’t you want to own a property

Solveig Rennan: They told our correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro about their homeowning journey to the modest North Minneapolis duplex they now own…living in one unit with plans the rent the other

Melva Luckett: We wanted to be able to, you know, have her be able to play outside, have a yard sale, take in the backyard and, you know, play out and sign the front and have a home for her for her generation.

Fred de Sam Lazaro: She wants to be on that right now.

Melva Luckett: Yes, she does

Fred de Sam Lazaro: So you want to you see this as a means of building a savings and building wealth, basically.

Tim Luckett: Yeah, for sure. Building wealth just with the equity that can go into your home. These are things that we just if we didn’t go to honestly, we didn’t go to the church that we went to, we wouldn’t have known about why it’s important to have a home. We we weren’t it wasn’t like we were not saying that our parents didn’t have homes, but it wasn’t like we were taught to why it was important to actually own a home, like the importance of it. Just having your family, the memories. And and that’s that’s another thing. Just the memories of your home on top of the money and the equity that you put into your house and what you can get out of it. I feel like we just wasn’t taught it and we really wanted it. Once we found out how important it is

Fred de Sam Lazaro: It’s part of actually building a family and sort of a spiritual sense in some ways that helps. Did you grow up in in rental housing, both of you or each of you?

Melva Luckett: I did not. My parents owned a home. Pretty much until I went off to college.

Fred de Sam Lazaro: Okay.

Tim Luckett: I mean, I had to have been renting until I was probably in about, I think sixth or seventh grade one of those. And then when I graduated, my mom, so she she sold her house and she moved. So, yeah, it wasn’t my whole life. But I know we stayed in houses and stuff my entire life that I can think of. I didn’t know that she owned until probably I was in high school and realized what it was. Yeah.

Fred de Sam Lazaro: So when you got here, when you finally managed to close on this house, was it the dream home or did you have to make compromises?

Tim Luckett: Compromises for sure. It was a big compromise, big sacrifice because of the value of these houses now and how much the prices are jacked up. It’s just like I feel like we didn’t get a duplex, something that we could build wealth in and invest. And I feel like it wouldn’t have been no ceiling for us to go if we would have just jumped right into a big home. It’s like, where do you you know, where do you go from that? I wanted to grow into a house and just keep growing as my family grows instead of going and get this big house and pay all this money that it’s not even worth. Just to say we got a big house like no. So we definitely sacrificed to come here.

Solveig Rennan: The Lucketts are a success story – but they’re the exception, not the rule. Lilricka Barber and her son, Malik, are ready to transition from renting to homeowning.

Lilricka Barber: Me and my son, he’s almost a teenager, so he needs his own space. A nice backyard, a basement where I can have an office as well as work space as well as my son can have a space to just be a boy instead of being cooped up in his room all day like he is here, a backyard. Because I love having family get togethers. I love hosting and cooking for my family, for having a nice sized backyard because my son wants a dog as well. So that’s a seller for me.

Solveig Rennan: Lilricka has struggled through abuse, addiction and homelessness, and worked for years to build credit and get her finances in order.

Lilricka Barber: I’m in a seven hundred, I can say. When I first started repairing our credit maybe five years ago, I was like in the five hundreds and that’s horrible. That’s not even on the chart, to be honest with you. So I’m in the low seven hundreds and I’m really I’m really proud of myself

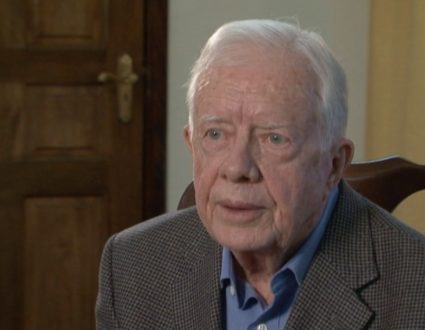

Solveig Rennan: Fred spoke to Minnesota Housing Commissioner Jennifer Ho about housing inequalities and policy in the state—plus the challenges Black renters in particular face as they try to become homeowners.

Jennifer Ho: I mean, a black indigenous households of color have paid more than 30 percent of their income, they’ve been cost burdened, as we say, in what they pay for rent for a long time. And as we see wages stagnate and housing prices continue to go up, the amount of your income that’s required just to pay your rent is increasingly a burden for folks. Combine that with the fact that both the pandemic and the economic impacts of the pandemic have hurt black and Latinx households significantly. It it’s not a surprise that black renters are disproportionately behind. We’re seeing that in terms of who’s applying for our rental MFA program. We’re also seeing that black homeowners are more likely to be in forbearance, be behind in their mortgage payments. So I think there’s. Before covid, we saw a kind of discrimination in terms of who was hurt most in the housing market as it existed covid we saw covid itself discriminate. We saw the economic impacts of covid discriminate. And so it really is just really put into a clear frame that we have to have targeted interventions to help black homeowners, black renters, others who are hurting because of the pandemic. And we’ve got federal resources to do that work.

Fred de Sam Lazaro: By that token, is your job as a Minnesota agency that much more difficult because you were starting out with a problem that was more pronounced in Minnesota? That is to say, the gap between white and nonwhite homeownership and just stable housing is a gap that much. Is your job that much harder now, given all of the circumstances and the aggravation, the complication of COVID?

Jennifer Ho: I I guess what I would say is that what we’ve learned at Minnesota Housing prior to covid is that when we intentionally set out to increase our lending to first time home buyers of color and we change what we do, how we do it and who we do it with, we saw a remarkable change in our outcomes. We have more than doubled the percentage of our first time homebuyers that use our mortgage products who are black, indigenous and household color because our production is also going up. That also means we’ve tripled the actual number that we saw last year in terms of our mortgage products. I you know, I think whether it’s renters or it’s homeowners, I think that this requires intentionality and it requires intentionality because we didn’t get here by accident. A whole bunch of stuff happened over the course of the last hundred hundred and twenty years, go back to go back to statehood decisions that were made to disadvantage some people and discourage people from becoming homebuyers, especially in the African-American community. And then we had home buyers. We had 50 percent of of black households were homeowners back in nineteen fifty. Then we went and built some interstates right through neighborhoods that had black middle class. And so these are policies that were whether they were kind of explicitly done or not, but they were intentionally done and it really decimated homeownership in the black community here. And so it is going to require decades of intentional work in order to to bring that number back up and bring it up so that it’s on par with white homeownership here in Minnesota. I, I think the opportunity right now is that there is a federal congressional conversation around housing is infrastructure. The president is talking about housing is infrastructure. We’ve heard the president talk about potentially having a federal down payment assistance program. Other tools that we learned at Minnesota Housing make a huge difference. I mean, the way that we accumulate wealth in America is largely through our homes. And if you weren’t allowed to buy in more affluent neighborhoods, if you weren’t given preferential pricing on your mortgage, if you bought a home and you had it taken away through eminent domain to build a freeway, if your home was appraised or is rising in value at a lower rate because of where it’s located, you have been disadvantaged over and over and over by the housing market in terms of your ability to accumulate wealth and pass that on to future generations.

Solveig Rennan: History has held many obstacles in the path toward homeownership for Black Minnesotans. One of the most concrete barriers were racial covenants

Kirsten Delegard: So racial covenants are clauses that were inserted into property deeds and reserved those certain parcels of land for the exclusive use of white people. And they were there were thousands and thousands of them used in the Twin Cities alone. They were used in every community across the country, and they really laid the foundation for the segregated communities that we are living in today in the United States.

Solveig Rennan: Fred spoke to Kirsten Delegard, who leads the University of Minnesota’s Mapping Prejudice Project—which is working to document and map out discrimination in housing.

Kirsten Delegard: So as a historian, I was interested in answering the question of how did the Twin Cities develop, develop some of the largest racial disparities in in the country? So I would say until last year, the Twin Cities really enjoyed this reputation as very progressive community. And and yet when you looked at the numbers, the numbers didn’t really support this progressive reputation. So I was interested in using historical tools to figure out how we got to the place that we are today. And of course, once you start looking at racial disparities, housing takes center stage. A lot of these other disparities that people have been talking about for years in terms of education, health, wealth are all rooted in what your access to housing is. So that led me to look at what were the historic housing policies that shaped the environment that we’re living in today. And one of the policies, one of the practices that jumped out was the use of racial covenants.

Fred de Sam Lazaro: Were your findings surprising to you?

Kirsten Delegard: Up until the time that we started doing this very granular mapping of racial covenants, scholars had not been able to answer some certain very basic questions about racial covenants, like how many were there, how much land did they cover, who did they target, what was the language of of these deeds? So we were surprised in some communities, in some neighborhoods where we were told that there would be racial covenants, they didn’t appear. We were surprised to see who they they targeted. It was we had heard about racial covenants a lot in the Jewish community. They were very few of them actually specifically mentioned Jews. But one hundred percent of these racial covenants were aimed at black people. So so that was I mean, that last part is not surprising. But we were surprised at how relentless the campaign that campaign was against black land tenure, against black homeownership through these documents.

Fred de Sam Lazaro: Was there a time when this actually started or really took off in recent history? Give us a sense of when this started to happen.

Kirsten Delegard: So the first racial covenants in the United States that’s been uncovered was actually in the eighteen forties on the East Coast, but they were relatively rare until the late 19th century, early 20th century. The first racial covenant that we found here was in it was put into place in 1910. And that’s where you really see racial covenants take off across the country in a in an organized way. And that has to do with the growth of the real estate industry. So the real estate industry was professionalizing in in those years. This was the same years that you had the formation of the National Association of Real Estate Agents. And they really saw that organization in particular, really saw these covenants as a tool that they could use to create what they saw to be harmonious communities, which had everything to do with race. They were reflecting a widespread conviction that for for neighborhoods to be harmonious, for them to be healthy, for them to be prosperous, they had to be racially homogenous. And and they fastened on racial covenants as a really effective tool to make that happen.

Fred de Sam Lazaro: Do you think that that the value of people’s homes was a major consideration? Talk a little bit about how that factors into all of this. The people who may not white people, that is to say, who may not consider themselves particularly racist, still want to protect the value of their homes. And there’s a perception that the advent of black people or people of color into the community is going to bring property values down. That’s a concern widespread. Does it become a self-fulfilling prophecy of the day?

Kirsten Delegard: Yeah, that that is a great question, because, of course, you have a lot of if you look at the historical record in particular, you have a lot of I’m not racist, but, you know, and it’s important to recognize that the main way that American families build wealth, build financial security for their families and pass that wealth on to the next generation is through homeownership. And so it feels like a very high stakes decisions for a lot of families. A lot of families are going to do a lot of things to make sure that they can acquire a home that they feel like will gain value over time. And so, yes, that was one of the and if you’re told all the time that the influx but that’s the language that was used, the influx of a of a person who was not white into your neighborhood would bring down your property value, that that was a real source of anxiety for for for for individual people who maybe did not see themselves as racist. And I and I would say, even though when you look at the historical record, you certainly see some very outspoken, outspokenly racist people. I think in many ways they’re the minority and it’s the structures that are way more important in terms of determining the actions of individual white people than a particular animus towards people who don’t look like them.

Fred de Sam Lazaro: Have you seen any difference in the way your work is received, whether your work is affected in a post the George Floyd Incident, murder?

Kirsten Delegard: Yeah, the Mappin Prejudice team in the in the wake of George Allen’s murder, we were we felt grateful that we could serve a role in in the aftermath because people from I mean, hundreds of people from all over the world started contacting us to understand why this happened in Minneapolis, why, you know, scholars are calling the the social movement that that has grown in the wake of George Floyds murder, the largest social movement in American history in terms of 20 million Americans took to the streets. And I think a lot of people were surprised that it came out of Minneapolis. But for those of us who have been working on this topic, I wish I could say I was surprised that this kind of racial reckoning started in Minneapolis, because this is the kind of thing that we have been warning about since the project started. You know, that the profound damage that structural racism is, is inflicting on our and our on our community. So since since George Floyds murder, we have engaged in I mean, we’ve had thousands of new volunteers join our project. We we had expected our mapping of Ramsey County, the covenant’s in Ramsey County, to take three years. It took eight months because we had such an upsurge of volunteers. We’ve had hundreds of requests for for talks and I and lots of media interviews. And, you know, to me, it shows this desire that people have to understand structural racism to understand how we got to this place. And and I would never say that racial covenants are the only reason that the Twin Cities are the way they are. But they’re a big piece. They’re a big part of the story. And they really help, especially white people who have never had a personal experience with rracism being the target of racism. They really help them to understand when people say it’s structural, it’s not you know, it’s not just implicit bias. It’s not just how do I feel or what do people say, but it’s the way racism is baked into our foundational institutions, our foundational documents. And so I really and what I’ve seen from from the people I’ve been talking to is a real commitment to trying to dismantle that, to trying to dig into whatever institution they’re they’re involved with, to use the tools that they have and and try to to to turn to to move in a different direction.

Solveig Rennan: Remember Lilricka Barber? After years of work to repair her credit, she was finally approved for a mortgage…

Fred de Sam Lazaro: what you’ve looked at, how many property?

Lilricka Barber: Over two hundred. Two hundred.

Solveig Rennan: Her big hurdle now: the market reality of tight supply and all-cash buyers, mostly investors who’ve outbid her for the few homes she could afford to bid on.

Lilricka Barber: We would get our hopes up and find something that was possible for us. And we get shot down.

Solveig Rennan: I checked in with Lilricka in February of 2022 as we were finishing up this podcast… and she’s still looking for a home. Our interviews were originally featured in our story called the Racial Gap in Homeownership, which aired on PBS NewsHour on August 13, 2021. To check out the full story, go to undertoldstories.org. This episode was hosted and edited by me, Solveig Rennan, and produced by Simeon Lancaster. The interview was conducted by our director Fred de Sam Lazaro. You can find every Under-Told: Verbatim episode, virtual reality 360 experiences and our entire library of Under-Told news reports from around the world at undertoldstories.org. Under-Told: Verbatim is brought to you by the Under-Told Stories Project based at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota. As always, thanks for your support.

“The way that we accumulate wealth in America is largely through our homes.”

Buying a home is a rite of passage, a life-changing step—but in the Twin Cities especially, this crucial key to accumulating and passing down wealth is much harder to come by if you are Black. Just 25 percent of Black residents of Minneapolis and St. Paul own their homes. That’s far below the national average, especially considering the Twin Cities are widely regarded as one of the country’s most affordable metros. As far as white residents here, though, 75 percent are homeowners. This episode of Under-Told: Verbatim includes interviews with new homeowners Tim and Melva Luckett, aspiring homeowner Lilricka Barber, Minnesota Housing Commissioner Jennifer Ho and historian Kirsten Delegard, who leads the Mapping Prejudice Project.