GWEN IFILL: Next, bringing business services to small-scale farmers in East Africa. Our story is part of a series called Food for 9 Billion. It’s a partnership with the Center for Investigative Reporting, American Public Media’s Marketplace, and Homelands Productions.

Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Andrew Youn was almost done with business school in 2005 when he took a brief vacation to Kenya. It was the Minnesota native’s first exposure to the irony of life for millions of people in rural Africa.

ANDREW YOUN, founder, One Acre Fund: The shocking thing and kind of an amazing paradox is that most of the world’s hungry people are actually farmers and their profession is to grow food. And the reason they’re not succeeding right now is they’re still using tools and techniques that literally date to the Bronze Age.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: He decided to apply his new MBA skills to see if he could help. He began with a pilot project to assist 40 families.

I took $7,000 of my own savings and bought seed and fertilizer and hired some local staff. And we gave it a shot. The families just kind of signed up. And they were also interested. And they had the best harvest of their entire lives in that first season. And right when that happened, I knew that there was something there.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: His project turned into One Acre Fund, named after the small size of most African subsistence farms. Six years later, a staff of more than 800 serves over 125,000 farm families in Kenya, Rwanda and Burundi.

ANDREW YOUN: If you look at those bales of seed, for example, that stack of bales is enough to change the lives of thousands of farm families with, you know, like more than 10,000 children living in those families.

The sheer magnitude of what we can accomplish from a humanitarian perspective with very little resources is just staggering.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: But One Acre Fund isn’t a typical humanitarian service. It offers a business model. One Acre gives the smallest of farmers the same services available to the biggest of businesses, credit, seed, insurance and access to markets.

It’s called the market bundle. One Acre Fund also offers training, how to space plants, when to apply fertilizer and how much. It’s not rocket science, but the results are impressive.

I’m standing in a spot that illustrates the difference One Acre Fund can make. Over my left shoulder is a pretty typical small holder farm where you’ll find a cluster of pretty randomly planted cornstalks. But walk just a few feet to that farmer’s neighbor, and you will find a One Acre Fund member. And this farmer’s seeds are of better quality. They’ve been planted in careful rows. And you can tell by the quality of the stalks and the sheer density of this plot that the yield here is going to be much higher.

Better harvests begin with better seeds and fertilizer that the farmers get at a discount.

ANDREW YOUN: The individual small holder farmer is about the least powerful person on the planet, you can imagine. But when we aggregate 100,000 of them or more together, then we get a lot of purchasing power and we can get them a good deal, we can deliver, we can add a lot of value to them.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: But, even with a good deal, cash is hard to come by here, especially at the start of the season. So instead of making the farmers pay up front, One Acre Fund gives them loans for the seeds and fertilizer they need, loans that are insured.

ANDREW YOUN: Poor people are of the worst suited people in the world to have risk in their lives. They’re already living on the margin. And having a bad harvest, for example, and bad weather basically means it could be as severe as a child or even two dying. So, rain insurance is a standard part of our package. And so if the rain doesn’t fall, they don’t pay.

Another risk is death. We have what we call funeral insurance.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The loans must be repaid at harvest time. But most farmers begin paying their installments well in advance. The default rate is less than 1 percent.

ANDREW YOUN: Wow. Congratulations.

So, this lady was saying that she was getting a milk cow. And she’s selling now, earning about $2, $2 a day from that milk cow.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: In Rwanda, Agriculture Minister Agnes Kalibata likes the fact that even though One Acre Fund is a nonprofit, it works with farmers as business partners.

AGNES KALIBATA, Rwandan agriculture minister: There’s always a sense of dependency. When they’re offering the private sector, there’s a sense of — it’s a give-and-take. So, One Acre Fund brings that on the table.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The approach is showing results. On average, farmers enrolled in One Acre Fund have seen their crop yields triple.

Joyce and Maurice Soita have done much better than average.

JOYCE SOITA, One Acre Fund farmer: For now, we have 18, but. . .

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Before.

JOYCE SOITA: . . . before, two or three bags.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So, before, you used to get two or three bags of maize from your land, and now you get 18 last year.

JOYCE SOITA: Eighteen, yes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: The Soitas took me to see the investments they have made with their profits, school for their four daughters, about 160 U.S. dollars per year.

JOYCE SOITA: My first kid, she say that she wants to be a doctor. Then I told her, keep up.

(LAUGHTER)

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Keep up. Yes, keep up that ambition.

JOYCE SOITA: Yes.

ANDREW YOUN: Our farmers go from subsistence to finally getting enough food for their entire families, but then also selling surplus for the first times in their lives.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: And Youn says this is opening up new opportunities for farmers.

Richard Sitati has been a One Acre Fund farmer for three years. He not only has surplus food staples like maize, but also grows crops for cash: peanuts and bananas. In the old days, Sitati had to rely on middlemen in his local market here in Twele for everything: buying seeds, selling the occasional surplus, with little bargaining power.

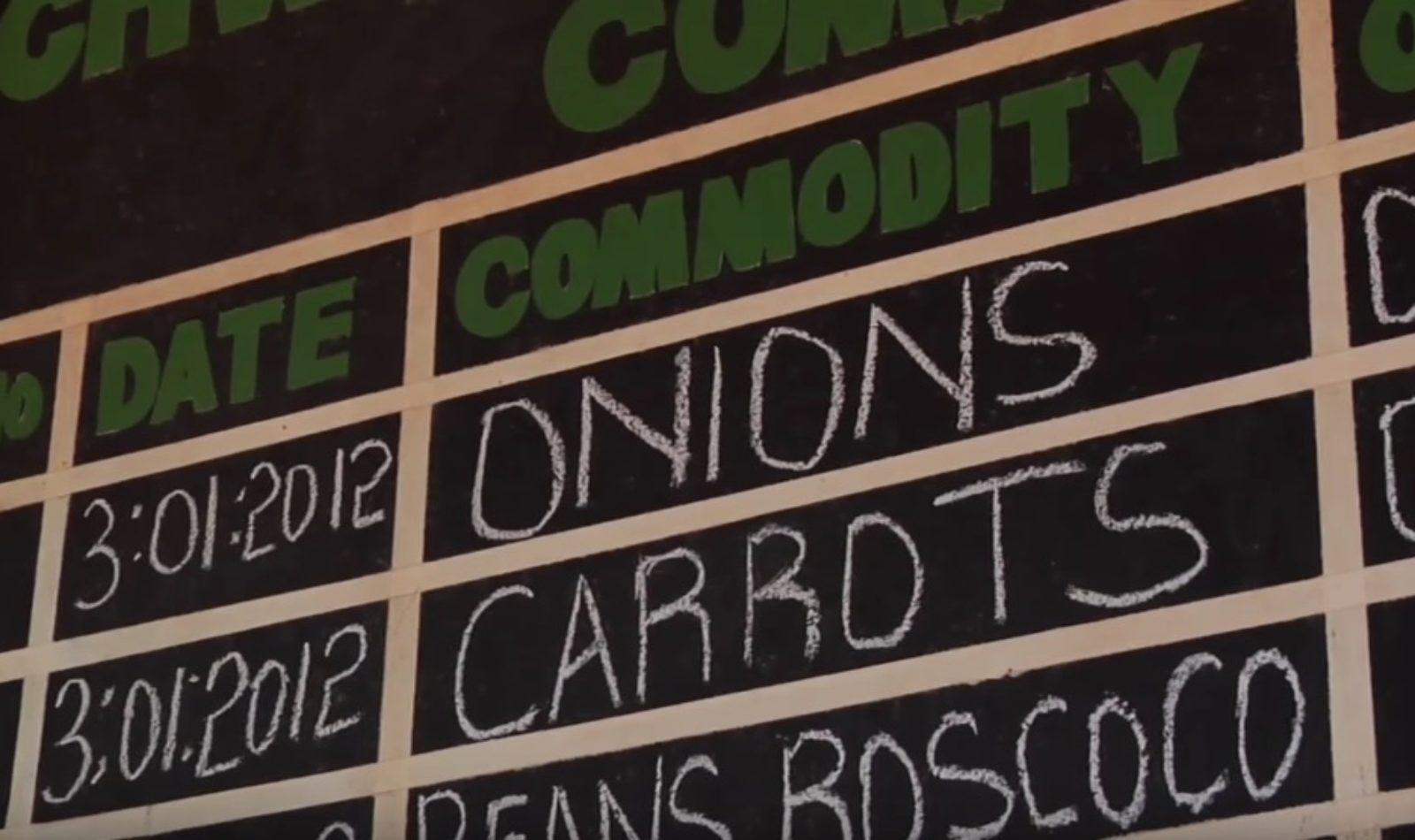

Now he visits a new kind of stall in the market. It sells information. Bananas, he learned, were fetching much higher prices in El Dorat, a town about 100 miles away.

RICHARD SITATI, One Acre Fund Farmer: So, here, I found out, when you look at the bananas, in Twele it’s 280.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Yes. Yes.

RICHARD SITATI: But when you go to El Dorat, it’s about 400.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So you can look at this board here and determine where the best place is to sell?

RICHARD SITATI: Yes. Yes. Yes.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: A new for-profit company called KACE has set up outlets like this one in markets across Kenya. The Internet and cell phone connections inform the trading boards and link producers like Sitati with distant buyers.

KACE was started by an Adrian Mukhebi, an economist trained at the University of Kansas. Mukhebi says the centers faced resistance when they first opened.

ADRIAN MUKHEBI, founder, Kenya Agricultural Commodity Exchange: Middlemen and traders didn’t like them. They opposed them. Why? Because we were providing information to the farmers. We were empowering the farmer to know the market prices and increase the farmers’ bargaining power.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Now he says, even though middlemen get a smaller share of the pie, the pie has gotten much larger.

For farmers, getting the best price is also a question of timing. Soon after a harvest, there’s plenty of maize, so the price plummets. One Acre staffers, most of them just out of college, are working on a pilot project that would offer loans for farmers to store some of their grain.

MAN: A farmer normally is selling their maize in January. We wanted, just basically, instead of them selling their maize, have it put right back in their house and then pay that school fee.

ANDREW YOUN: The farmer would be very tempted to sell their harvest almost immediately, so they could pay for school fees. But really they ought to be holding onto that harvest for about six months, when it’s much more valuable and scarcer in the hunger season.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: So they’d get a better price for it.

ANDREW YOUN: Exactly.

MAN: If we can help our farmers store their maize for longer, then we can help them make a lot more money.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: One Acre Fund took in $5 million in farmer loan revenue last year, but still needed a million dollars in grants and donations to cover their expenses.

They say their Kenya and Rwanda operations should break even in a few years. But sustainability also depends on the investments that governments will make, from building new roads to improving storage facilities and seed and fertilizer supply.

At the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, Margaret Kroma says the government support is critical for groups like One Acre Fund to succeed.

MARGARET KROMA, Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa: Otherwise, we can have beautiful, wonderful islands of excellent work that just fades away over time. How do you make that ultimate connection between the technology that works in smaller assistance and the larger policy environment, the institutions that will ensure that these innovations continue to be scaled up and scaled out?

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Andrew Youn agrees. But for now, the program’s success is built on the farmers’ success, one acre at a time.

ANDREW YOUN: It’s really wonderful to see. People really do invest every dollar they finally gain and start building kind of like a staircase to a better life.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Youn predicts One Acre Fund will exceed its goal to serve 1.5 million farm families by 2020, a 15-fold increase from today, but still a fraction of the 40 million families that he says could use help across Africa.

JUDY WOODRUFF: Fred’s reporting is a partnership with the Under-Told Stories Project at Saint Mary’s University in Minnesota.

A Community Investment

In Kenya, Rwanda and Burundi, a new approach to small-scale farming has spread to more than 100,000 families in just four years. Part of the Food for 9 Billion series, Fred de Sam Lazaro reports on an organization called One Acre Fund that brings struggling farmers together, offering them training, resources and market access.

Related Links

Feeding Farmers

Most of the world’s hungry people are actually farmers and their profession is to grow food. Many of them are still using tools and techniques that literally date to the Bronze Age.

Andrew Youn

“The individual small holder farmer is about the least powerful person on the planet, you can imagine. But when we aggregate 100,000 of them or more together, then we get a lot of purchasing power and we can get them a good deal, we can deliver, we can add a lot of value to them. … The sheer magnitude of what we can accomplish from a humanitarian perspective with very little resources is just staggering.”